Serverless technologies have a lot of people excited - in theory, they offer infinite scaling with no maintenance. After mostly seeing “hello-world on Lambda” tutorials, I was curious how it would work for a real application with a frontend and a database.

This article reviews my experience using AWS Lambda for full-stack web applications. If you’re familiar with the theory and want to know more about how it works in practice, you’re in the right place.

Why serverless

Serverless could be a good choice for anyone who doesn’t want to manage infrastructure. Specifically, it’s a great fit for bursty workloads that need to scale in short bursts (why pay for a server to idle all day?), and for functions that need to run every time an item enters a queue.

A typical web app is none of the above, yet that’s what I cover in this post. I wanted to try deploying a web app with zero maintenance. For a side project, Heroku wasn’t worth the money and monitoring & maintaining a server wasn’t worth my time. So I gave Lambda a shot.

I built this project using Flask, ReactJS, and Postgres, and if you squint hard enough, it looks like a production system. While I can only share my experience, I believe it can be generalized to any Python backend and perhaps beyond.

Zappa

Zappa is a library that makes it easy to deploy Python applications to Lambda. Lambda expects a zip archive of your code and your Python dependencies. With a couple commands, Zappa creates the archive and much more, including the Lambda function, IAM roles, and API gateway.

Zappa hooks into your virtualenv in order to zip up the Python dependencies. Many popular libraries, such as numpy, include compiled C code for performance. When you pip install numpy, you get compiled binaries for your current environment - MacOS in my case. These binaries likely won’t work on Lambda, which runs on a Linux environment. So it’s clear that naively packaging a virtualenv won’t work. To remediate this, Zappa has a sister repository of precompiled binaries for popular Python packages and it swaps these in when building the archive. If you use a dependency with compiled binaries that isn’t on this list, it might not work on Lambda - depends on your development environment. In this case I recommend using Docker to create the archive (see below).

Zappa addresses cold starts by periodically invoking the Lambda function to keep a server warm. This fixes one of the most common complaints with serverless functions wherein requests are slow after the app hasn’t been used in a while.

Here I’ll go over how to handle a few common use cases with Zappa:

Deploy application code

More or less just follow the docs.

pip install zappain your virtualenv (if you don’t use virtualenv, keep reading)- Run

zappa initto get azappa_settings.jsonfile. Mine looks like this for a Flask app:

{

"dev": {

"app_function": "src.app.app",

"profile_name": null,

"project_name": "my-project",

"runtime": "python3.7",

"s3_bucket": "my-bucket",

"aws_region": "us-east-2",

"exclude": ["node_modules", "package*.json"]

}

}

I recommend using exclude to keep the size of your archive down. Zappa supports large projects but don’t be tricked into thinking you need this, when in reality your archive is full of non-Python code.

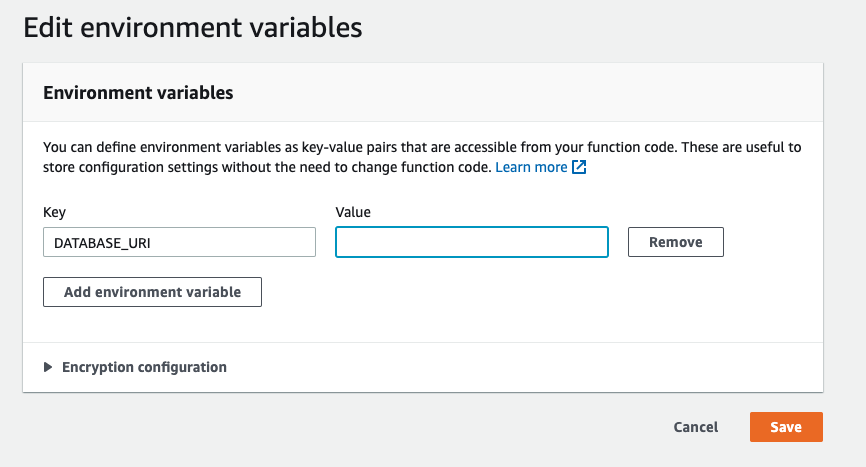

Store secrets

Most web apps don’t exist in isolation; they need to talk to other services, such as a database, and need to store secrets to do this. If you have a small number of secrets that don’t change often, the most straightforward approach is to set them in the Lambda console.

This makes the values available in the Lambda runtime environment, so you can read them into your application like normal:

import os

DATABASE_URI = os.environ.get(

"DATABASE_URI", "postgresql://postgres:postgres@postgres:5432"

)

If you have too many secrets and prefer to manage them programmatically, you can also write them to a file in S3 that your service reads and extracts the values from at startup.

Init / migrate the database

Now that we have the DB secrets available, we want to initialize and migrate the database. I used Amazon RDS for my DB. While it’s possible to spin up an EC2 instance and run the migration commands there, that defeats the purpose of not having to manage servers. Zappa allows you to run any function in your app using zappa invoke, so let’s use that.

- First you need the function to execute in the right VPC and with the appropriate security groups that allow it to connect to the DB. I had to add this the

"dev"section of myzappa_settings.json:

"vpc_config" : {

"SubnetIds": [ "my-subnet" ],

"SecurityGroupIds": [ "my-security-group" ]

}

- Next, run the script. I started with

zappa invoke dev 'db_utils.create_schema_and_tables'to initialize the schema and tables, andzappa invoke dev 'db_utils.seed_db'to seed the DB with some testing data. You can run a similar command to migrate the DB. Make sure those functions connect to the DB using the environment variables mentioned above.

For Django projects, Zappa supports execution of management commands.

Serving static files

A common setup for web apps is to serve the frontend and backend on the same server. There’s a reverse proxy web server, such as nginx, that sits in front of the WSGI / ASGI Python server. The reverse proxy, which is very fast, will serve the static files itself and forward other requests to the Python server.

Since requests for static files never hit the Python code, these files could be served from some other location.

With Lambda, you don’t have access to the underlying web server and therefore can’t give special treatment to static files. This leaves you with two options:

- Serve the static files through Python code, which may be slow

- Serve the static files from a separate service, like S3 or CloudFront

Either should work, but I went with option 2 because it’s clean, easy, and performant.

There are many guides on the internet for static web hosting using S3, so I won’t repeat them here. However, I’ll zoom into a couple issues that are often left out.

Server side rendering

Single page applications (SPAs) typically send the client a Javascript bundle that creates the HTML for the app. Since not all web crawlers can execute Javascript code, the crawlers only see a barebones HTML page that says “load App.js”. This means websites that are rendered exclusively on the client will struggle with SEO, since search engines cannot index all of their content.

To improve this people use server-side rendering (SSR), where some or all of the HTML is rendered on the server. This makes the site SEO-friendly and faster for the initial page load.

Server-side rendering usually means you need a Node.js backend that can execute JavaScript code. While it looks possible to do SSR with a Python backend, I’m not sure if Lambda gives you enough control to set that up. You should investigate more before committing down this path.

Client side routing

SPAs use client-side routing to prevent full page reloads as the user navigates through the site. When a user clicks on a link to get a “new page”, the page itself remains the same but JS replaces the contents of it.

With static hosting in S3, client-side routing works mostly as expected…until you refresh the page when you aren’t on the home page. The browser sees a URL like /foo and looks for foo.html in the S3 bucket. This file doesn’t exist since the contents of the page are created by Javascript running in the browser.

There are a couple solutions: set the error document to index.html or configure the routing rules.

CORS

Since your frontend and backend live on different servers, you’ll need to enable cross-origin resource sharing on the backend server. This is straightforward with existing plugins like Flask-Cors.

Debugging

Logs are available in CloudWatch, but I recommend running zappa tail and keeping it open while developing to get the latest logs. You can also configure an exception handler function that will send unhandled exceptions to your application monitoring tool.

One word of caution: Zappa’s default is to time out if a function doesn’t return output within 30 seconds. The timeout messages are generic and easy to miss. So if you start seeing weird behavior, it’s possible something timed out. For example, I saw a post about how someone’s migration script takes >30 seconds to run, so Zappa timed it out and it didn’t finish migrating the DB. Look out for this and configure the setting accordingly.

Docker users

I like developing in Docker containers. They’re portable and I have the assurance that my development environment is exactly the same as the production environment. Related to this, I have two gripes about Lambda / Zappa:

-

If you aren’t developing on Linux, your development environment will be different than the runtime environment.

-

Although Lambda allows building the package from Docker, Zappa only works with virtualenvs. This adds an extra step as I have to create a virtualenv, whereas normally I

pip installdirectly into the container.

As mentioned above, Zappa maintains a list of precompiled binary extensions and swaps out your binaries for Lambda-compatible equivalents. This is usually fine. However, you might find yourself using a dependency that ships with binary extensions but isn’t popular enough to make the list. Then you’ll wish for a better development environment.

Docker to the rescue! There’s a Zappa Docker Image, which is based off of the LambCI Lambda Docker Image that provides a Lambda-like environment in Docker. You can use it as your base image.

In the future, I hope Lambda will accept an arbitary Docker image. Other clouds already do this.

Conclusion

This article was a brain dump of what I learned using Zappa, and I hope it was useful for you. We talked about when to use Zappa and how to migrate a DB, store secrets, serve a frontend, and get a reproducible dev environment.

I recommend Zappa for individuals or small teams that want to focus on application code instead of infrastructure. It was great for deploying a side project to the internet and not having to monitor it. If nobody pings my web app until a year from now, it should still be there and I’ll have paid almost nothing for compute. At scale, cost becomes a consideration and managing a cluster still makes sense.

If you have any comments, message me on Twitter! I’d love to hear about your experience using Lambda and Zappa.